2017-05-07T14:02:16+02:00

Some of the first computers found their employment in performing the myriad calculations of the Manhattan project, and the first monolithic integrated circuit found its first customer in the US air force, whose missile guidance systems pushed the limits of both raw power, and miniaturization.

“Had Hegel’s philosophy of history embraced this age, Hitler’s robot-bombs would have found their place beside the early death of Alexander and similar images, as one of the empirically selected facts by which the state of the world-spirit manifests itself directly in symbols. Like Fascism itself, the robots career without a subject. Like it they combine the utmost technical perfection with total blindness. And like it they arouse mortal terror and are wholly futile. – “I have seen the world-spirit,” not on horseback but on wings and without a head, and that refutes, at the same stroke, Hegel’s philosophy of history.”

Adorno’s awareness in this fragment of Minima Moralia, presumably written at some point between 1944 and 1949, is so sharp that it prefigures the symbol that the cold war era pivoted upon - the H-bomb. Wernher Von Braun, largely responsible for Hitler’s robot bombs, transitioned smoothly into building robot bombs in New Mexico, finally producing the world’s first nuclear ballistic missile.

It was largely the work of the rocket scientists of Peremunde, eagerly snapped up by the Americans and the Soviets, that the world would live in the shadow of, until the end of the Cold War. Like the V2 rockets, the nuclear ballistic missiles of the next half century epitomized the fusion of technical mastery with blindness, each new generation more perfectly fusing terror to futility, until even their hypothetical use was, ultimately, mass suicide.

It’s telling that, at this time, political reason developed into ‘Game Theory’, a technical methodology that the USA used to make navigate the utter senselessness of nuclear war. As headless and futile as the bombs themselves, it was so utterly simplistic that even the crude computers of the time could authoritatively assert that, at one point or another, it is reasonable to burn the entire earth to a stub.

To my knowledge, Adorno never wrote anything about Game Theory, which developed and grew to prominence in the later years of his life, but it’s hard to imagine whether he would have reacted with horror or laughter.

While, at the time, documentaries imagined their ‘supercomputers’ could do anything from provide strategic direction, to medical diagnoses, to psychological insight1, it’s clear in retrospect this was an absurd overestimation of the capacities of the computers of the time. Even today, with data-entry, hardware, and programming techniques that are orders of magnitude more powerful than they were even in the 90s, it’s a challenge to produce a program that can reliably recognize a number.

The ‘psychological profiles’ of these early computers were of the order of a text file and an index that served instead of a search function, search functions being both beyond early computer’s limited processing capacities, and largely unnecessary, since they didn’t have much stored anyway.2

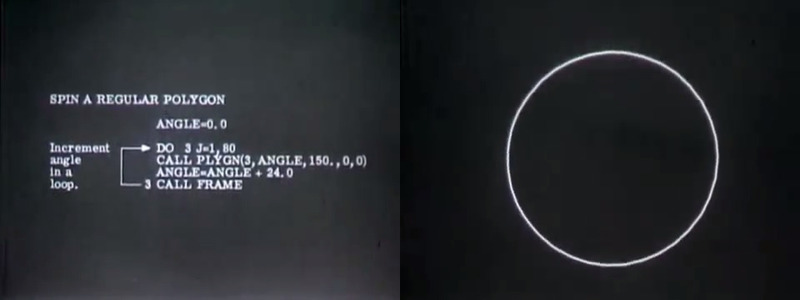

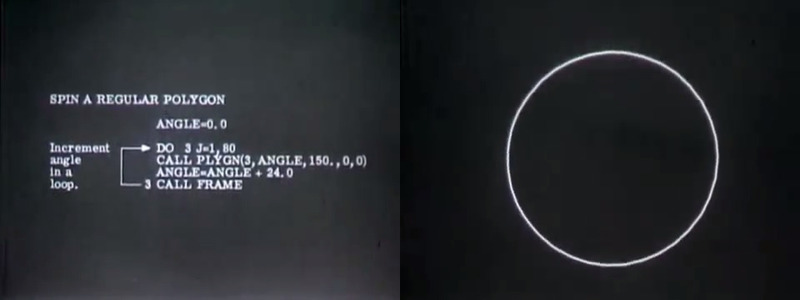

You can even find ‘simulations’ of spaceflight, rendered in crude, hand-programed CRT line drawings, where even drawing a square was a technical challenge - and the actual simulation work was largely possible to do by hand, or at least, with mechanical computers.

Fantasies often outstrip reality, but the point at which the ‘calculus of deterrence’ was worked out with ‘utter objectivity’ by computers that, ultimately, had less transistors than a brain-damaged dog has neurons, was probably the historical high point.

Perhaps the most interesting thing about computers is the way in which they mesh fantasy with reality at a fundamental level. It is a basic fact of discourse that reality is immune to it - dumb matter cannot be convinced, or persuaded, but only moved.

In a sense, computers break this paradigm, yielding logic, a kernel of discourse, from coils of litz wire, etched silicone wafers, and spinning magnetic drums. If there are ‘no real triangles’, as Nietzsche put it once, there should also be no real XOR gates. The fact that there are, and that you can do maths with them, and can in fact calculate the hypotemuse of a triangle, just as Socrates taught the slave boy, is a deeply disturbing fact.3

The persistent fantasies about AI4 present one way to resolve this uncanny break of the subject-object paradigm - if one could assert that computers are in some way qualitatively similar to humans, then they can learn trigonometry because they are like us.

The problem here, obviously, is that the computers they pinned these fantasies on were clunky amalgams of hand-soldered chips, bigger than your apartment, and less powerful than a phone.

The more reasonable response would be to simply assert that humans are qualitatively identical to matter, and therefore to argue that discourse itself extends from matter, and logic itself is as available to rocks, and dogs, and asteroids, as it is to humans.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Plx8YtYmizc↩︎

since the most advanced memory storage technique of the time (‘core rope memory’) could contain about 70 KB per square foot, and most computers ran on magnetic drums, that would contain an average of 10KB of memory. To put this in context, a kilobyte is roughly equivalent to a million-character text file, which is a bit less than three books.↩︎

A Nietzschean can obviously retreat one step back, and just say that a mechanical XOR is not a real XOR - but I think this is unsatisfying. When Nietzsche wrote there are no real triangles, you could read that as a straight, empiricist observation. Now, that’s not possible).↩︎

It’s worth noting that in the 70’s, computer scientists assumed AI was just around the corner, with ‘rule-based’ AI. Predictably, the effort failed, and the bottom dropped out from all the research projects, leaving the subject next-to-dead until fairly recently.↩︎